san sabÁ and the world

Globalization today is presented as a new problem. Yet in the Eastern hemisphere there had always been communication and mutual influence among medieval “world systems”—the civilized centers of economic and cultural activity. Those connections attained new levels once Europeans discovered the Americas and attained world hegemony. They mapped the globe and established regular maritime lines of communication. The archaeology of San Sabá witnesses this new world order.

Metalwork shows the influence of medieval Europe in decorative motifs such as heraldic lions. But there is relatively more copper and less iron, reflecting the copper working expertise of the indigenous people of Mexico, the direct source for many San Sabá artifacts.

The ceramics reveal international connections. A game piece has been made from a fragment of Chinese porcelain, the product of a trade network that involved a regular system of Manilla galleons shipping Spanish Reales minted from American silver to the East in return for oriental goods. “Olive jar” pottery from Spain demonstrates direct contact with the Old World. Another pattern is shown by Majolica decorated pottery, which had been highly developed in late medieval Spain but which found a new center of production at Puebla in Mexico where skilled local potters manufactured it in a variety of shapes and colors.

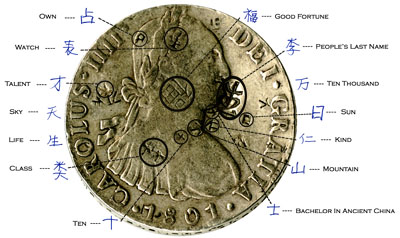

[above] Spanish coin diagramed to show Chinese marks made each time the coin was traded. On loan from Dr. Allan Keuthe.

Currency also made it way around the world. “Spanish dollars” (often called pieces of eight, because they were worth eight reales) were minted from the late fifteenth to the nineteenth century. Manufactured in the Americas from American silver, they became the major currency of international trade. When they circulated in East Asia, they often acquired verification marks from Chinese trading houses and merchants, as in the example shown. Such coinage would have originally paid for the porcelain found at San Sabá. Although today we associate pieces of eight with pirate lore, we are indebted to them in a more practical way—the real de a ocho is an ancestor of the American dollar. This Spanish coin was legal tender in the United States until 1857. The two pillars of Hercules that flank the royal arms on the back have been suggested as the origin of the double bars of the dollar sign $. Pieces of eight were sometimes physically cut up into pieces of “two bits” and “four bits,” the first quarters and half dollars.