Musical instruction: old world and new

The Guidonian Hand in the Middle Ages in the New World

Guido of Arezzo (d. after 1033), an Italian monk, is one of the world’s most famous music teachers. In four surviving, short, unsystematic works, he presents a wide range of techniques–some invented, some borrowed–by which he claims it is possible to teach music to even the most tone-deaf young boys. To the bishop of Arezzo he claimed to be such a good teacher, that “even boys of your church should surpass in the practice of music the fully trained veterans of all other places” (Guido, Micrologus).

Among his methods were the use of a line staff for writing music, where letters of the alphabet designate the pitches of the lines; the original “do re mi” method of teaching pitch; and the “Guidonian hand,” a visual mnemonic device by which young musicians could be taught to sing medieval notation by associating each note-name with a joint of the left hand, and, in more complicated versions, to visualize the scales used in various types of Church chants.

Guido’s original “Do Re Mi” was actually “Ut Re Mi.” These musical syllables sound like nonsense to us, but Guido created them by taking the first syllables of the phrases of a hymn to St. John.

The ancient hymn prays “So that

your servants may sing the marvel of your actions with free strings, remove

the sin from their polluted lips, O Saint John,” but Guido may have tweaked

the ascending melody, which is not previously attested, in order to make it

fit his “ut re mi” system for teaching the notes. The “do” of the “do re

mi” Americans use today, does not appear until 1635 in Italy, and it took

many more decades to replace the original version.

The ancient hymn prays “So that

your servants may sing the marvel of your actions with free strings, remove

the sin from their polluted lips, O Saint John,” but Guido may have tweaked

the ascending melody, which is not previously attested, in order to make it

fit his “ut re mi” system for teaching the notes. The “do” of the “do re

mi” Americans use today, does not appear until 1635 in Italy, and it took

many more decades to replace the original version.

[left] Depiction of a Guidonian hand, found in a Franciscan Guide for Novices, the Regola de n.s.p.s. Francisco y breve declaracion de su preceptos, 1725. From the Mathes Collection.

Music and notes could be taught by the “Guidonian hand,” a device popularized by Guido, that makes the alphabetized notes, and chords based on them easily accessible. Instructors throughout the Middle Ages considered this harmonic hand to be one of the best ways to teach singing.

The Guidonian Hand in the Middle Ages in the New World

The missionaries who reached the Western hemisphere brought with them their sacred music and their methods of teaching it. Music was one of their major forms of prayer. However, it also turned out to be a popular technique of evangelization because the indigenous peoples had their own developed musical traditions, vocal and instrumental, and music provided points of contact and communication between very different civilizations and cultures.

A musical culture had to be constructed. The Franciscans systematically brought their medieval methods to new peoples. Their missions in New Spain generally included libraries and schools. Spain and Mexico supplied instruments--strings, brass, and woodwinds--and written music. The most gifted residents were often organized into choirs and orchestras, sometimes attaining considerable proficiency.

The role of Spain in bringing its music to the New World is illuminated by materials in the Archive of the Indies that were located by researchers working out of Texas Tech University in Seville.

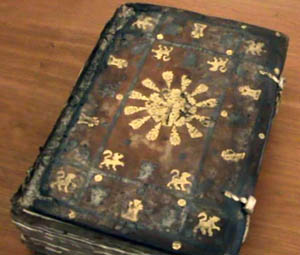

[right]

Pictured is a legajo (a bundle of documents, here elegantly bound) which

contains papers related to San Sabá. An inventory of items shipped to the

presidio mentions guitars, violins, fiddle bows, and drums.

[right]

Pictured is a legajo (a bundle of documents, here elegantly bound) which

contains papers related to San Sabá. An inventory of items shipped to the

presidio mentions guitars, violins, fiddle bows, and drums.

Although these instruments could have been used in ecclesiastical processions outside of church, and the drums might have had military applications, their primary purpose must have been recreational. Even in a far off presidio where life was hard and supply lines long, the Spanish government saw music as an essential part of life.

Missionaries used the medieval “Guidonian hand.” In New Spain’s handbook for Franciscan novices, immediately following an explication of the liturgy of the Mass, appears a section on singing. It introduces the seven letters that Guido had used to designate notes of the scale. Then it presents a harmonic hand, here labeled the “Manus Aretina,” the “Arezzo hand,” in honor of Guido of Arezzo.

Institutionalization -- San Saba -- Mission -- Presidio -- Music -- Globalization